POTENTIAL ENEMY

by Mack Reynolds

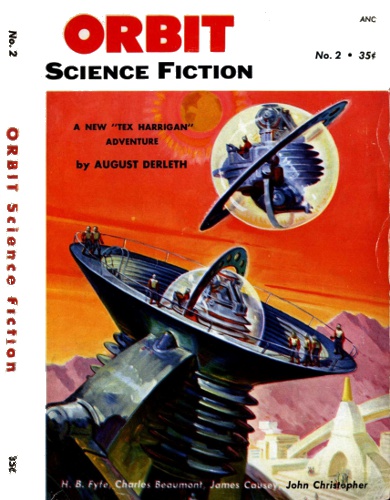

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Orbit volume 1number 2, 1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence thatthe U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CAESAR HAD THE SAME PROBLEM AND NEVER SOLVED IT. LORDHELP US IF IT JUST CAN'T BE DONE!

Alexander the Great had not dreamed of India, nor even Egypt, when heembarked upon his invasion of the Persian Empire. It was not a matter ofbeing like the farmer: "I ain't selfish, all I want is the land thatjines mine." It was simply that after regaining the Greek cities of AsiaMinor from Darius, he could not stop. He could not afford to havepowerful neighbors that might threaten his domains tomorrow. So he tookEgypt, and the Eastern Satrapies, and then had to continue to India.There he learned of the power of Cathay, but an army mutiny forestalledhim and he had to return to Babylon. He died there while making plans toattack Arabia, Carthage, Rome. You see, given the military outlook, hecould not afford powerful neighbors on his borders; they might becomeenemies some day.

Alexander had not been the first to be faced with this problem, nor washe the last. So it was later with Rome, and later with Napoleon, andlater still with Adolf the Aryan, and still later—

It isn't travel that is broadening, stimulating, or educational. Not thetraveling itself. Visiting new cities, new countries, new continents, oreven new planets, yes. But the travel itself, no. Be it by themethods of the Twentieth Century—automobile, bus, train, oraircraft—or be it by spaceship, travel is nothing more than boring.

Oh, it's interesting enough for the first few hours, say. You look outthe window of your car, bus, train, or airliner, or over the side ofyour ship, and it's very stimulating. But after that first period itbecomes boring, monotonous, sameness to the point of redundance.

And so it is in space.

Markham Gray, free lance journalist for more years than he would admitto, was en route from the Neptune satellite Triton to his home planet,Earth, mistress of the Solar System. He was seasoned enough as a spacetraveler to steel himself against the monotony with cards and books,with chess problems and wire tapes, and even with an attempt to do anarticle on the distant earthbase from which he was returning for theSpacetraveler Digest.

When all these failed, he sometimes spent a half hour or so staring atthe vision screen which took up a considerable area of one wall of thelounge.

Unless you had a vivid imagination of the type which had remained withMarkham Gray down through the years, a few minutes at a time would havebeen enough. With rare exception, the view on the screen seemed almostlike a still; a velvety blackness with pin-points of brilliant light,unmoving, unchanging.

But even Markham Gray, with his ability to dream and to discern thatwhich is beyond, found himself twisting with ennui after thirty minutesof staring at endless space. He wished that there was a larger number ofpassengers aboard. The half-dozen businessmen and their women andchildren had left him cold and he was doing his best to avoid them. Now,if there had only been one good chess player—

Co-pilot Bormann was passing through the lounge. He nodded to thedistinguished elderly passenger, flicked his eyes quickly,professionally, over the vision screen and was about to