EMINENT AUTHORS

OF THE

NINETEENTH CENTURY.

LITERARY PORTRAITS

BY

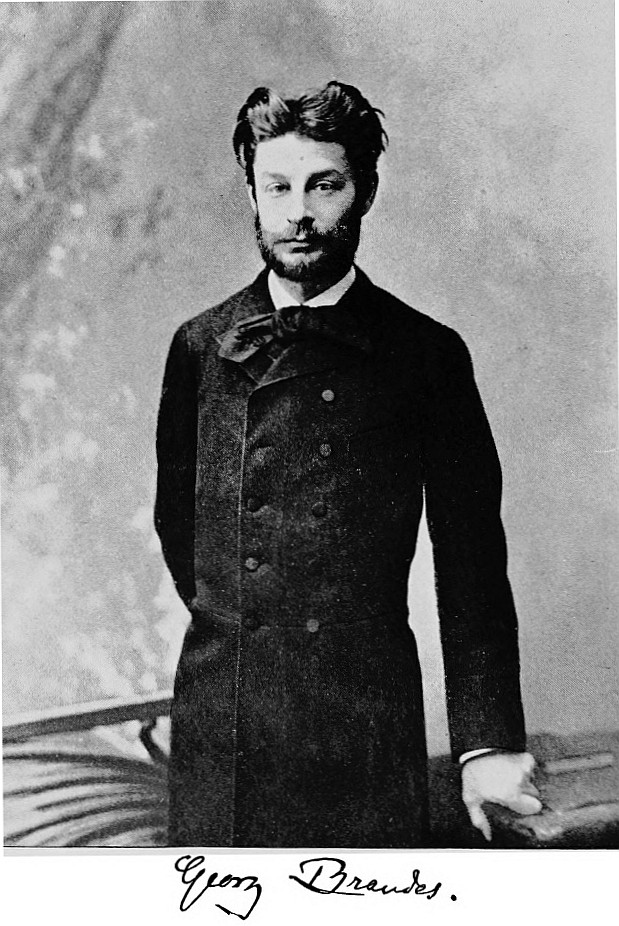

Dr. GEORG BRANDES

TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL BY

RASMUS B. ANDERSON,

UNITED STATES MINISTER TO DENMARK; AUTHOR OF "NORSE MYTHOLOGY,"

"VIKING TALES OF THE NORTH," "AMERICA NOT DISCOVERED

BY COLUMBUS," AND OTHER WORKS.

NEW YORK:

THOMAS Y. CROWELL & CO.

1886

NOTE.

This volume is published by special arrangement with the author. At myrequest Dr. Georg Brandes has designated me as his American translatorand takes a personal interest in the enterprise.

To Auber Forestier, who kindly aided me in translating the stories ofBjörnstjerne Björnson, I have to express my cordial thanks for valuableassistance in the preparation of this translation.

RASMUS B. ANDERSON.

COPENHAGEN, DENMARK,

July, 1886.

AUTHOR'S PREFACE.

It is a well-known fact that at the beginning of this century severalprominent Danes endeavored to acquire citizenship in German literature.Since then the effort has not been repeated by any Danish author. Tosay nothing of the political variance between Germany and Denmark,these examples are far from alluring on the one hand, and on theother hand they furnish no criterion of the Danish mind. The greatremodeler of the Danish language, Oehlenschläger, placed his worksbefore the German public in German so wholly lacking in all charm,that he only gained the rank of a third-class poet in Germany. Thesuccess, however, which lower grades of genius, such as Baggesen andSteffens, have attained, was the result, in the first case, of averitable chameleon-like nature and a talent for language that wasunique of its kind, and in the second, of a complete renunciation ofthe mother-tongue.

The author of this volume, who is far from being a chameleon, and whohas by no means given up his native tongue, who stands, indeed, in themidst of the literary movement which has for some time agitated theScandinavian countries, knows very well that a human being can onlywield a powerful influence in the country where he was born, wherehe was educated by and for prevailing circumstances. In the presentvolume, as in other writings, his design has simply been to write inthe German language for Europe; in other words, to treat his materialsdifferently than he would have treated them for a purely Scandinavianpublic. He owes a heavy debt to the poetry, the philosophy, and thesystematic æsthetics of Germany; but feeling himself called to bethe critic, not the pupil, of the history of German literature, hecherishes the hope that he may be able to repay at least a smallportion of his debt to Germany.

The nine essays of which this book consists, and of which even thosethat have already appeared in periodicals, have been thoroughlyrevised, are not to be regarded as "Chips from the Workshop" of acritic; they are carefully treated literary portraits, united by aspiritual tie. Men have sat for them, with whom the author, with oneexception (Esaias Tegnér), has been personally acquainted, or of whomhe has at least had a close view. To be sure, the same satisfactorysurvey cannot always be taken of a living present as of a completedpast epoch; but perhaps a