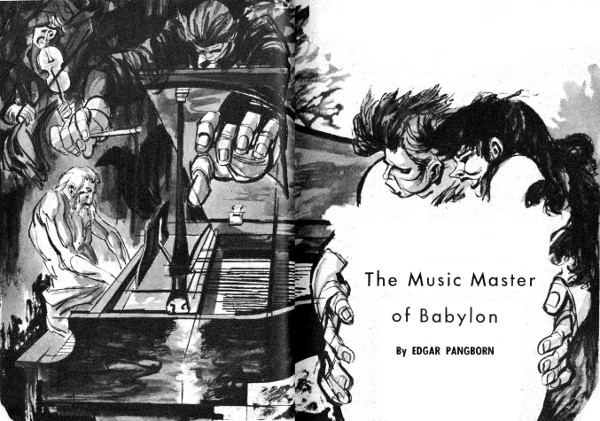

The Music Master of Babylon

By EDGAR PANGBORN

Illustrated by KRIGSTEIN

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction November 1954.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

What more fitting place for the last man on

Earth to live in than a museum? Now if only

he could avoid becoming an exhibit himself!

For twenty-five years, no one came. In the seventy-sixth year of hislife, Brian Van Anda was still trying not to remember a happy boyhood.To do so was irrelevant and dangerous, although every instinct of hisold age tempted him to reject the present and dwell in the lost times.

He would recall stubbornly that the present year, for example, was2096; that he had been born in 2020, seven years after the close of theCivil War, fifty years before the Final War, twenty-five years beforethe departure of the First Interstellar. (It had never returned, norhad the Second Interstellar. They might be still wandering, trifles ofMan-made Stardust.) He would recall his place of birth, New Boston,the fine, planned city far inland from the ancient metropolis that therising sea had reclaimed after the earthquake of 1994.

Such things, places and dates, were factual props, useful when Brianwanted to impose an external order on the vagueness of his immediateexistence. He tried to make sure they became no more than that—to shutaway the colors, the poignant sounds, the parks and the playgrounds ofNew Boston, the known faces (many of them loved), and the later yearswhen he had briefly known a curious intoxication called fame.

It was not necessarily better or wiser to reject those memories,but it was safer, and nowadays Brian was often sufficiently tired,sufficiently conscious of his growing weakness and lonely unimportance,to crave safety as a meadow mouse often craves a burrow.

He tied his canoe to the massive window that for many years had been aport and a doorway. Lounging there with a suspended sense of time, hewas hardly aware that he was listening. In a way, all the twenty-fiveyears had been a listening. He watched Earth's patient star sink towardthe rim of the forest on the Palisades. At this hour, it was sometimespossible, if the Sun-crimsoned water lay still, to cease grieving toomuch at the greater stillness.

There was scattered human life elsewhere, he knew—probably a greatdeal of it. After twenty-five years alone, that, too, often seemedalmost irrelevant. At other times than mild evenings, hushed noons ormornings empty of human commotion, Brian might lapse into anger, fightthe calm by yelling, resent the swift dying of his echoes. Such moodswere brief. A kind of humor remained in him, not to be ruined by sorrow.

He remembered how, ten months or possibly ten years ago, he hadencountered a box turtle in a forest clearing, and had shouted at it:"They went thataway!" The turtle's rigidly comic face, fixed bynature in a caricature of startled disapproval, had seemed to point upsome truth or other. Brian had hunkered down on the moss and laugheduproariously—until he observed that some of the laughter was weeping.

Today had been rather good. He had killed a deer on the Palisades,and with bow and arrow, thus saving a bullet. Not that he needed topractice