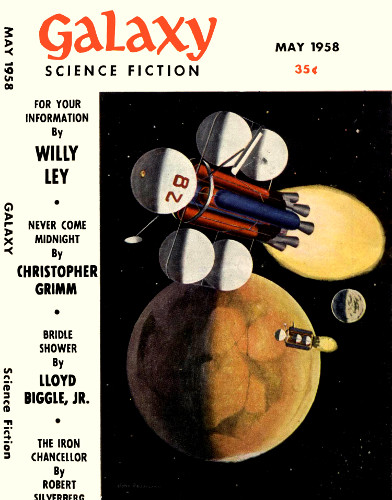

NEVER COME MIDNIGHT

by CHRISTOPHER GRIMM

Illustrated by DILLON

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction May 1958.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Across the void came a man who could not ever

have been born—from a world that could never

have been conceived—to demand his birthright

of an Earth that would have to die to pay it!

I

Jan Shortmire smiled. "You didn't know I had a son, did you, Peter?Well, neither did I—until quite recently."

"I see." However, Peter Hubbard knew that Jan Shortmire had nevermarried in all of his hundred and fifty-five years. In that day andage, unmarried people did not have children; science, the law, andpublic sophistication had combined to make the historical "accident"almost impossible. Yet, if some woman of one of the more innocentplanets had deliberately conceived in order to trap Shortmire, surelyhe would have learned of his son's existence long before.

"I'm glad it turns out that I have an heir," Shortmire went on."Otherwise, the government might get its fists on what little Ihave—and it's taken enough from me."

Although the old man's estate was a considerable one, it did seemmeager in terms of the money he must have made. What had become ofthe golden tide that had poured in upon the golden youth, Hubbardwondered. Could anyone have squandered such prodigious sums upon theusual mundane dissipations? For, by the time the esoteric pleasures ofthe other planets had reached Earth—the byproduct of Shortmire's ownachievement—he must have already been too old to enjoy them.

At Hubbard's continued silence, Shortmire said defensively, "If they'dlet me sell my patents to private industry, as Dyall was able to do,I'd be leaving a real fortune!" His voice grew thick with anger."When I think how much money Dyall made from those factory machines ofhis...."

But when you added the priceless extra fifty years of life to the moneyShortmire had made, it seemed to Hubbard that Shortmire had been amplyrewarded. Although, of course, he had heard that Nicholas Dyall hadbeen given the same reward. No point telling Shortmire, if he did notknow already. Hubbard could never understand why Shortmire hated Dyallso; it could not be merely the money—and as for reputation, he had ashade the advantage.

"That toymaker!" Shortmire spat.

Hubbard tactfully changed the subject. "What's your boy like, Jan?" Butof course Jan Shortmire's son could hardly be a boy; in fact, he wasprobably almost as old as Hubbard was.

Such old age as Shortmire's was almost incredible. Sitting there inthe antique splendor of Hubbard's office, he looked like a splendidantique himself. Who could imagine that passion had ever convulsed thatthin white face, that those frail white fingers had ever curved inlove and in hate? Age beyond the reach of most men had blanched thisonce-passionate man to a chill, ivory shadow.

For once, Hubbard felt glad—almost—that he himself was ineligible forthe longevity treatment. The allotted five score and ten was enough forany except the very selfish—or selfless—man.

But Shortmire was answering his question. "I have no idea what the boyis like; I've never seen him." Then he added, "I suppose you've beenwondering why I finally decided to make a will?"

"A lawyer never wonders when people do make wills, Jan," Hubbard saidmildly.