This ebook was transcribed by Les Bowler.

THE FALL

OF

PRINCE FLORESTAN OF MONACO.

BY HIMSELF.

London:

MACMILLAN AND CO.

1874.

[The Right of Translation andReproduction is reserved.]

p. 1THE FALLOF PRINCE FLORESTAN OF MONACO.

I am Prince Florestan of Wurtemberg, born in 1850, andconsequently now of the mature age of twenty-four. I might callmyself “Florestan II.” butI think it better taste for a dethroned prince, especially whenhe happens to be a republican, to resume the name that is inreality his own.

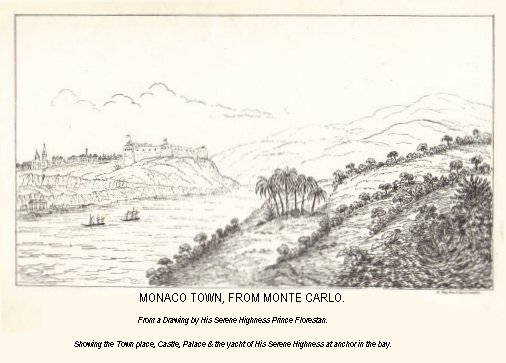

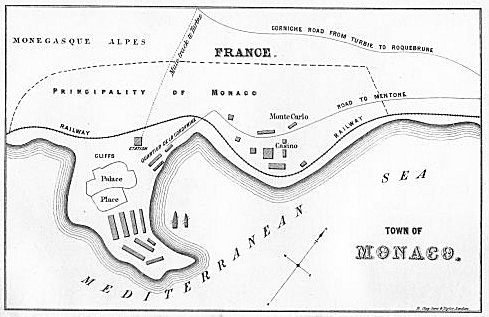

Although the events which I am about to relate occurred thiswinter, so little is known in England of the affairs of theEx-principality of p.2Monaco, now forming the French commune of that name, thatI feel that the details of my story, indeed all but the barefacts on which it is grounded, will be news to Englishreaders. The English Post Office believes that Monaco formspart of Italy, and the general election extinguished thetelegrams that arrived from France in February last.

All who follow continental politics are aware that the PrinceCharles Honoré, known as Charles III. of Monaco, and alsocalled on account of his infirmity “the blindprince,” was the ruling potentate of Monaco during the lastgambling season; that there lived with him his mother, thedowager princess; that he was a widower with one son, PrinceAlbert, Duc de Valentinois, heir apparent to the throne; that thelatter had by his marriage with the Princess Marie of Hamilton,sister to the Duke of Hamilton, one p. 3son who in 1873 was six years old;that all the family lived on M. Blanc the lessee of the gamblingtables. But Monaco is shut off from the rest of the worldexcept in the winter months, and few have heard of the calamitieswhich since the end of January have rained upon the rulingfamily. My cousin, Prince Albert, the “SailorPrince,” a good fellow of my own age, with no fault but hisrash love of uselessly braving the perils of the ocean, had oftenbeen warned of the fate that would one day befall him. Oncewhen a boy he had put to sea in his boat when a fearful storm wasraging, had been upset just off the point at Monaco, and had beensaved only by the gallantry of a sailor of the port who hadrisked his own life in keeping his sovereign’s sonafloat. In October 1873 my unfortunate cousin bought atPlymouth an p.4English sailing yacht of 450 tons. He had asailor’s contempt for steam, which he told me was only fitfor lubbers, when he came up and stayed with me at Cambridge inNovember to see the “fours.” He explained to methen that he had got a bargain, that he had bought his yacht forone-third her value, and that he was picking up a capital crew ofthirty men. He had no need to buy yachts for a third theirvalue, for he was rich enough