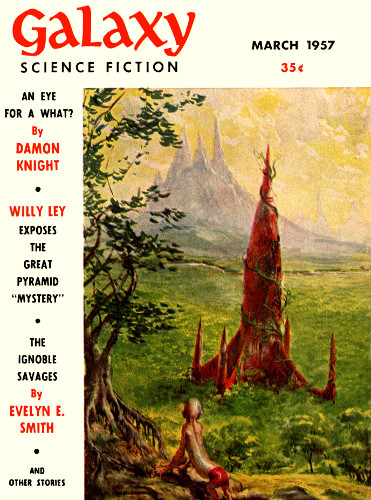

THE DEEP ONE

By NEIL P. RUZIC

Illustrated by DILLON

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction March 1957.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

There wasn't a single mistake in the plan for

survival—and that was the biggest mistake!

For centuries, the rains swept eight million daily tons of land intothe sea. Mountains slowly crumpled to ocean floors. Summits rose againto see new civilizations heaped upon fossils of the old.

It was the way of the Earth and men knew it and did not worry. The endwas always in the future. Ever since men first learned to make marks oncave walls, the end remained in the future.

Then the future came. The records told men how the Sun was before, sothey knew it was swollen now. They knew the heat was not always thishot, or the glacier waters so fast, the seas so high.

They adapted—they grew tanner and moved farther pole-ward.

When the steam finally rose over equatorial waters, they moved to thelast planet, Pluto, and their descendants lived and died and came toknow the same heat and red skies. Finally there came the day when theycouldn't adapt—not, at least, in the usual way.

But they had the knowledge of all the great civilizations on Earth, sothey built the last spaceship.

They built it very slowly and carefully. Their will to live becamethe will to leave this final, perfect monument. It took a hundred andfifty years and during all that time they planned every facet of itsoperation, every detail of its complex mechanisms. Because the ship hada big job to do, they named it Destiny and people began to think ofit not as the last of the spaceships, but as the first.

The dying race sowed the ship with human seed and hopefully named itsunborn passengers Adam, Eve, Joseph and Mary. Then they launched ittoward the middle of the Milky Way and lay back in the red light oftheir burning planet.

All this was only a memory now, conserved in the think-tank of amachine that raced through speckled space, dodging, examining,classifying, charting what it saw. Behind, the Sun shrank as once itswelled, and the planets that were not consumed turned cold in theirorbits. The Sun grew fainter and went out, and still the ship spedforward, century after century, cometlike, but with a purpose.

At many of the specks, the ship circled, sucking in records, passingjudgment, moving on—a bee in the garden of stars. Finally, hundredsof light-years from what had been its home, it located an Earth-typeworld, accepted it from a billion miles off, and swung into an approachthat would last exactly eighteen years.

Immediately, pumps delivered measured quantities of oxygen and nitrogenatoms. Circuits closed to move four tiny frozen eggs next to frozenspermatozoa. The temperature gradually increased to a heat oncemaintained by animals now extinct.

The embryos grew healthily and at term were born of plastic wombs.

The first voices they heard were of their real mothers. Soft, caressingsongwords. Melodious, warm, recorded women voices, each different,bell-clear, vivacious, betraying nothing of the fact that they weredead these long centuries.

"I am your mother," each voice told its belated offspring. "You can seeme and hear me and touch what appears to be me, and together with yourcousins, you'll grow strong and healthy...."

The voices sang on and the babies gurgled in their import