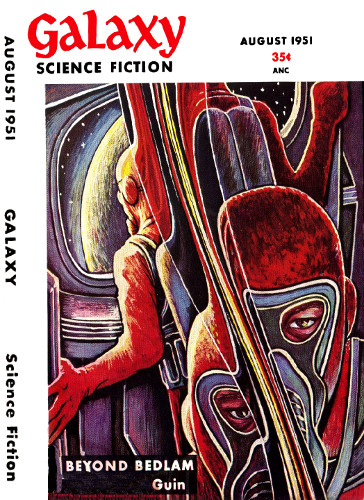

OPERATION DISTRESS

By LESTER DEL REY

Illustrated by WILLER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction August 1951.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Explorers who dread spiders and snakes prove that heroism

is always more heroic to outsiders. Then there's the case

of the first space pilot to Mars who developed the itch—

Bill Adams was halfway back from Mars when he noticed the red rash onhis hands. He'd been reaching for one of the few remaining tissues tocover a sneeze, while scratching vigorously at the base of his neck.Then he saw the red spot, and his hand halted, while all desire tosneeze gasped out of him.

He sat there, five feet seven inches of lean muscle and bronzed skin,sweating and staring, while the blond hair on the back of his neckseemed to stand on end. Finally he dropped his hand and pulled himselfcarefully erect. The cabin in the spaceship was big enough to permitturning around, but not much more, and with the ship cruising withoutpower, there was almost no gravity to keep him from overshooting hisgoal.

He found the polished plate that served as a mirror and studiedhimself. His eyes were puffy, his nose was red, and there were otherred splotches and marks on his face.

Whatever it was, he had it bad!

Pictures went through his head, all unpleasant. He'd been only a kidwhen the men came back from the South Pacific in the last war; but anuncle had spent years dying of some weird disease that the doctorscouldn't identify. That had been from something caught on Earth. Whatwould happen when the disease was from another planet?

It was ridiculous. Mars had no animal life, and even the thinlichenlike plants were sparse and tiny. A man couldn't catch a diseasefrom a plant. Even horses didn't communicate their ills to men. ThenBill remembered gangrene and cancer, which could attack any life,apparently.

He went back to the tiny Geiger-Muller counter, but there was no signof radiation from the big atomic motor that powered the ship. Hestripped his clothes off, spotting more of the red marks breaking out,but finding no sign of parasites. He hadn't really believed it, anyhow.That wouldn't account for the sneezing and sniffles, or the puffed eyesand burning inside his nose and throat.

Dust, maybe? Mars had been dusty, a waste of reddish sand and desertsilt that made the Sahara seem like paradise, and it had settled onhis spacesuit, to come in through the airlocks with him. But if itcontained some irritant, it should have been worse on Mars than now. Hecould remember nothing annoying, and he'd turned on the tiny, compactlittle static dust traps, in any case, before leaving, to clear the air.

He went back to one of the traps now, and ripped the cover off it.

The little motor purred briskly. The plastic rods turned against furbrushes, while a wiper cleared off any dust they picked up. There wasno dust he could see; the traps had done their work.

Some plant irritant, like poison ivy? No, he'd always worn hissuit—Mars had an atmosphere, but it wasn't anything a man couldbreathe long. The suit was put on and off with automatic machinegrapples, so he couldn't have touched it.

The rash seemed to get worse on his body as he looked at it. Thistime, he tore one of the tissues in quarters as he sneezed. The littlesupply was almost gone; there was never space enough for much beyondessentials in a spaceship, even wit