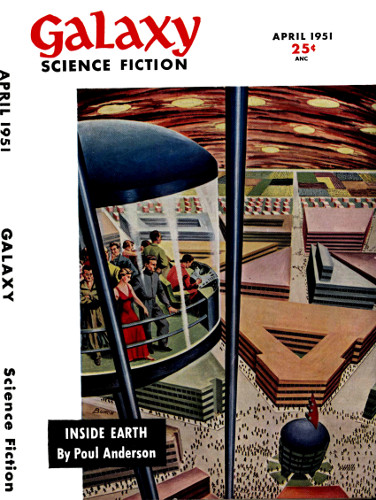

INSIDE EARTH

By POUL ANDERSON

Illustrated by DAVID STONE

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction April 1951.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Obviously, no conqueror wants his subjects to

revolt against his rule. Obviously? This one

would go to any lengths to start a rebellion!

I

The biotechnicians had been very thorough. I was already a littleundersized, which meant that my height and build were suitable—Icould pass for a big Earthling. And of course my face and hands and soon were all right, the Earthlings being a remarkably humanoid race.But the technicians had had to remodel my ears, blunting the tips andgrafting on lobes and cutting the muscles that move them. My crest hadto go and a scalp covered with revolting hair was now on the top of myskull.

Finally, and most difficult, there had been the matter of skin color.It just wasn't possible to eliminate my natural coppery pigmentation.So they had injected a substance akin to melanin, together with a viruswhich would manufacture it in my body, the result being a leatherybrown. I could pass for a member of the so-called "white" subspecies,one who had spent most of his life in the open.

The mimicry was perfect. I hardly recognized the creature that lookedout of the mirror. My lean, square, blunt-nosed face, gray eyes,and big hands were the same or nearly so. But my black crest hadbeen replaced with a shock of blond hair, my ears were small andimmobile, my skin a dull bronze, and several of Earth's languages werehypnotically implanted in my brain—together with a set of habits andreflexes making up a pseudo-personality which should be immune to anytests that the rebels could think of.

I was Earthling! And the disguise was self-perpetuating: the hairgrew and the skin color was kept permanent by the artificial "disease."The biotechnicians had told me that if I kept the disguise long enough,till I began to age—say, in a century or so—the hair would actuallythin and turn white as it did with the natives.

It was reassuring to think that once my job was over, I could berestored to normal. It would need another series of operations and asmuch time as the original transformation, but it would be as completeand scarless. I'd be human again.

I put on the clothes they had furnished me, typical Earthlygarments—rough trousers and shirt of bleached plant fibers, jacket andheavy shoes of animal skin, a battered old hat of matted fur known asfelt. There were objects in my pockets, the usual money and papers, aclaspknife, the pipe and tobacco I had trained myself to smoke and evento like. It all fitted into my character of a wandering, outdoors sortof man, an educated atavist.

I went out of the hospital with the long swinging stride of oneaccustomed to walking great distances.

The Center was busy around me. Behind me, the hospital and laboratoriesoccupied a fairly small building, some eighty stories of stone andsteel and plastic. On either side loomed the great warehouses, militarybarracks, officers' apartments, civilian concessions, filled with thevigorous life of the starways. Behind the monstrous wall, a mile to myright, was the spaceport, and I knew that a troopship had just latelydropped gravs from Valgolia herself.

The Center swarmed with young recruits off duty, gaping at the sights,swaggering in their new uniforms. Their skins shone lik