THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANDOCTRINE OF IMMORTALITY.

THE

Ancient Egyptian Doctrine

OF THE

Immortality of the Soul

BY

ALFRED WIEDEMANN, D.PH.

PROFESSOR OF ORIENTAL LANGUAGES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF BONN

AUTHOR OF

“ÆGYPTISCHE GESCHICHTE,” “DIE RELIGION DER ALTEN ÆGYPTER,”

“HERODOT'S ZWEITES BUCH”

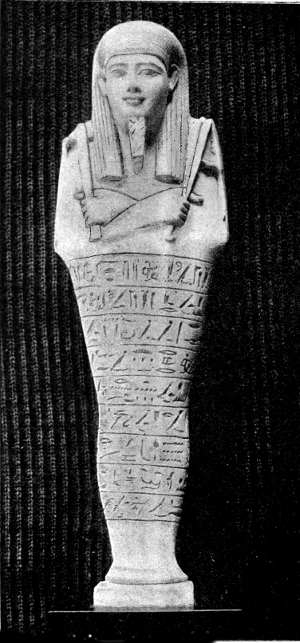

With Twenty-one Illustrations

LONDON

H. GREVEL & CO.

33, KING STREET, COVENT GARDEN, W.C.

1895

Printed by Hazell Watson, &. Viney, Ld., London and Aylesbury.

PREFACE.

IN writing this treatise my object has been togive a clear exposition of the most importantshape which the doctrine of immortality assumed inEgypt. This particular form of the doctrine wasonly one of many different ones that were held.The latter, however, were but occasional manifestations,whereas the system here treated of was thepopular belief among all classes of the Egyptianpeople, from early to Coptic times. By far thegreater part of the religious papyri and tomb textsand of the inscriptions of funerary stelæ are devotedto it; the symbolism of nearly all the amulets isconnected with it; it was bound up with thepractice of mummifying the dead; and it centredin the person of Osiris, the most popular of allthe gods of Egypt.

Even in Pyramid times Osiris had already attainedpre-eminence; he maintained this position throughoutthe whole duration of Egyptian national life,and even survived its fall. From the fourth centuryB.C. he, together with his companion deities, enteredinto the religious life of the Greeks; and homagewas paid to him by imperial Rome. Throughoutthe length and breadth of the Roman Empire, evento the remotest provinces of the Danube and theRhine, altars were raised to him, to his wife Isis, andto his son Harpocrates; and wherever his worshipspread, it carried with it that doctrine of immortalitywhich was associated with his name. ThisOsirian doctrine influenced the systems of Greekphilosophers; it made itself felt in the teachings ofthe Gnostics; we find traces of it in the writingsof Christian apologists and the older fathers of theChurch, and through their agency it has affectedthe thoughts and opinions of our own time.

The cause of this far-reaching influence lies bothin the doctrine itself, which was at once the mostprofound and the most attractive of all the teachingsof the Egyptian religion; and also in the comfortixand consolation to be derived from the patheticallyhuman story of its founder, Osiris. He, the sonof the gods, had sojourned upon earth and bestowedupon men the blessings of civilisation. At lengthhe fell a prey to the devices of the Wicked One,and was slain. But the triumph of evil and of deathwas only apparent: the work of Osiris endured, andhis son followed in his footsteps and broke the powerof evil. Neither had his being ended with death,for on dying he had passed into the world to co