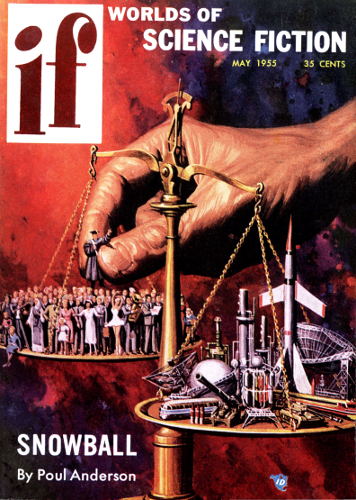

FIRTH'S WORLD

BY IRVING COX, JR.

His world was Utopia inhabited only by

wealthy, brilliant, creative, ambitious people;

it was the ultimate in freedom, exempt from

taxes, social problems, petty responsibilities....

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, May 1955.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Let him go. It's quite safe to leave us. I want to talk to him.

Sit over there, Chris, where you can be comfortable.

A paradox, isn't it? You were taught we may never go back. Now I'veauthorized the building of the rocket. From your point of view youwere justified in trying to destroy it. I'm violating the regulations;you weren't. But time changes the shape of the truth, Chris; it isn'tstatic. No one had the insight, then, to grasp the insanity of JohnFirth's dream. People hated Firth or envied him; but no one called himmad.

John Firth was an industrialist; yet far more than that,too—politician, scientist, financier, even an artist of sorts. Therewas nothing he couldn't do; and few things he didn't do superblywell. That accounts for his philosophy. He never understood his ownsuperiority. He honestly believed that all men could achieve what hehad, if they set their minds to it.

"Lazy, incompetent fools!" he would say. "The world's full of them. Andthey've elected a government of fools, taxing me to support the others."

As billionaires go, John Firth was very young. Six months after WorldGovernment became an established reality, Earth ships began to explorethe skies; and in less than a year Mars, Venus and the Earth had formeda planetary confederacy.

A new feeling came to men when the burden of war-fear was lifted fromtheir minds. Men were free—free for the first time in centuries. Theirfull energies were channeled into invention, exploration, experiment.The Earth was like a frontier town: booming, uproarious, lusty,dynamic—but with a social conscience: poverty and deprivation for noneand unlimited opportunity for all. For Man—that abstract symbol ofmass humanity—it was the best of all possible worlds. Yet there weremisfits; John Firth was one of them.

"We're coddling people," he said. "We're teaching them to live oncharity, on government hand-outs—and I'm expected to pay for it all.Cut them loose; let them sink or swim for themselves. If some of themdon't survive—well, they won't; that's all. We'd be a stronger peopleif we could rid ourselves of the leeches."

He was a man of the new age,—stubbornly holding to ideas from the old.

And then the Stranger came to see him. We don't know who the Strangerwas or where he came from. A force of evil, perhaps—the symbol ofSatan refurbished and streamlined to fit the concepts of the modernworld.

"I've been reading your political pamphlets, Mr. Firth," the Strangersaid. "You hold rather—rather fascinating views."

"Now that I'm suitably flattered," Firth answered, "may I ask whatparticular form of hand-out you want?"

"None. I've something for sale." The Stranger took a pamphlet out ofhis pocket. "But tell me this, first: do you honestly believe whatyou've written here?"

"Every word of it. If I could find my sort of world anywhere in theuniverse, I'd pull up stakes in a minute and—"

"You can create your own world, Mr. Firth."

"Do you suppose I haven't tried? In every election I back my candidateswith all I have—prestige, propaganda, mone