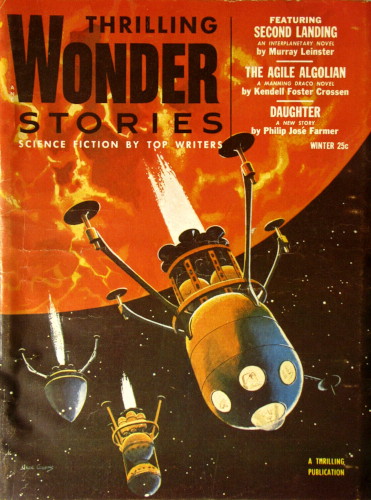

Second Landing

A Novel by

MURRAY LEINSTER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Thrilling Wonder Stories Winter 1954.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I

The exploring-ship Franklin made its first landing on a remarkablewide beach on the western coast of Chios, the largest land-mass onThalassia. Using the longest axis of the continent as a base, and thepointed end as seen from space as 0°, this beach bears 246° from themedian point of the base-line.... The Franklin later berthed inlandsome four miles 360° from Firing Plaza Number One on the chart. Thereis a pleasant savannah here, with a stream of water apparently safefor drinking.—Astrographic Bureau Publication 11297, Appendix toSpace Pilot Vol. 460, Sector XXXIV, pg. 58-59.

It was not plausible that Brett Carstairs should find a picture ofa girl, to all appearances human, in millenia-old ruins on a planetsome hundreds of lightyears from earth. But the whole affair wasunlikely, beginning with the report of the exploring-ship whichcaused the Thalassia-Aspasia Expedition in the first place. Had itnot been for the photographs and the ceramic artifacts, nobody wouldhave believed that report. It simply was not credible that anotherintelligent race should have ever existed in the galaxy. No hint ofextra-terrestrial reasoning beings had been found in two centuries ofexploration. But the exploration-ship's stilted narrative didn't stopat one impossibility. It said that on the twin worlds Thalassia andAspasia, revolving perpetually about each other as they trailed thesatellite-sun Rubra on its course, not one, but two, intelligentraces had existed. It offered some evidence that some thousands ofyears before they had fought, bitterly and mercilessly, and that theyhad exterminated each other in an interplanetary atomic war whichlasted only days or even hours. It was hard to believe.

But the picture of the girl was more impossible than anything else.Brett didn't believe it. He didn't quite dare mention it until thething was all over.

He didn't find it at the very beginning, of course. There werepreliminaries. The Thalassia-Aspasia Expedition was handicapped fromthe start by the lack of funds. The general public was much moreexcited about colonization of nearby planetary systems than researchon a planet that wouldn't be colonized in a thousand years. So theExpedition was very small—no more than a dozen members altogether—andit landed on Thalassia from an Ecology Bureau ship. It would be pickedup in six months or so. Probably. Even then, what it found might notmatter to anybody else.

Brett joined up because it was his only chance at adventure and becausehis hobby warranted his inclusion in the staff. He could drive a flier,of course—everybody could—but he'd specialized in palaeotechnology,the study of ancient industrial processes. If there really had beenan intelligent race or races out in space, he would make betterguesses than most at how its machinery operated and what its factoriesproduced. But his personal reason for going was an anticipatory feelingof excitement at the idea of being left with a small group of humanbeings on a planet where even the skies were unfamiliar, and wherethey would be more terribly alone than any similar group had ever beenbefore.

That excitement lasted during the tedious journey in overdrive andduring the long a