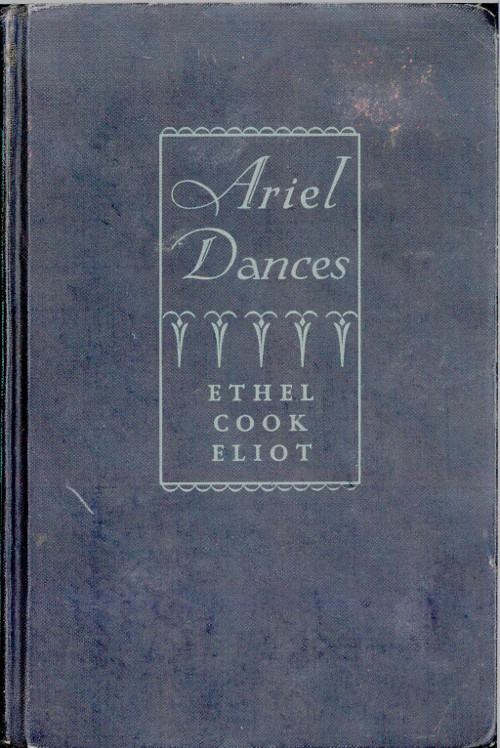

Ariel Dances

by

Ethel Cook

Eliot

Boston

Little, Brown,

and Company

1931

Copyright, 1931,

BY ETHEL COOK ELIOT

All rights reserved

Published February, 1931

Reprinted February, 1931 (three times)

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FOR

MY MOTHER

Ariel Dances

Chapter I

Ariel, quiet but alert, lay in her steamer chair, one ofthe most inconspicuous of the several hundred passengers theBermuda was bringing to New York. No one would be likelyto look at her twice or give her a second thought, as she crouchedaway from the March wind, insufficiently protected from thecold by her nondescript tweed coat, and carelessly, casually bare-headed.All about her on the deck were people of outstanding,vivid types. The thing that had impressed Ariel about these fellowpassengers during the two days of the voyage was theirapparent self-sufficiency,—a gay, bright assurance of their ownsignificance, and the reasonableness, even the inevitableness, oftheir being what and where they were. The very children appearedto take it quite as a matter of course that they shouldcome skimming over the Atlantic in a mammoth boat-hotelwhile they played their games, read their books and ate theirmeals,—just like that.

Ariel took nothing as a matter of course, and she never hadfrom the minute of earliest memory. Her proclivity to wonderand to delight was as organic as her proclivity to breathe. Butnow it was neither delight nor wonder but an aching suspensethat quivered at the back of her mind. She thought, “If Fatherwere here! If it weren’t alone, this adventure! New York Harborat last! I—Ariel! But it isn’t real. There’s no substance. Itwas to have happened and been wonderful, but this is palerthan our imagining of it. The shadow of our imagining. Oh, it’sI who have died and not Father. Where he is, whatever he isdoing, it’s still real with him. With Father it would be alwaysreal,—alive.”

A steward came up the deck, carrying rugs and a book forthe woman who had occupied the chair next to Ariel’s duringthe two days’ voyage. Two children with their nurse trailed behind.Ariel’s glance barely touched the group and returned toNew York’s terraced, dream-world sky line. But she was gladthat these people had come up on deck and would be near herduring the little while left of ship life. It did not matter thatthey would remain unaware of her until the very end. It wasmore interesting, being interested in them, than having theminterested in her. And there was no reason on earth why theyshould be interested in her. It never entered Ariel’s head thatthere was.

Joan Nevin, the woman, was tall, copper haired and eyelashed,and graceful with a lithe, body-conscious kind of gracefulness,of fashion, perhaps, more than of nature. Her sleek furcoat, her high-heeled, elegant pumps—even the close dark hat,flaring back from her copper eyebrows—these seemed to motivateher gait and her postures. She was, perhaps, more pliableto them than they to her. But Ariel did not mind this, althoughshe realized it. It was wonderful, in its way, fascinating bystrangeness.