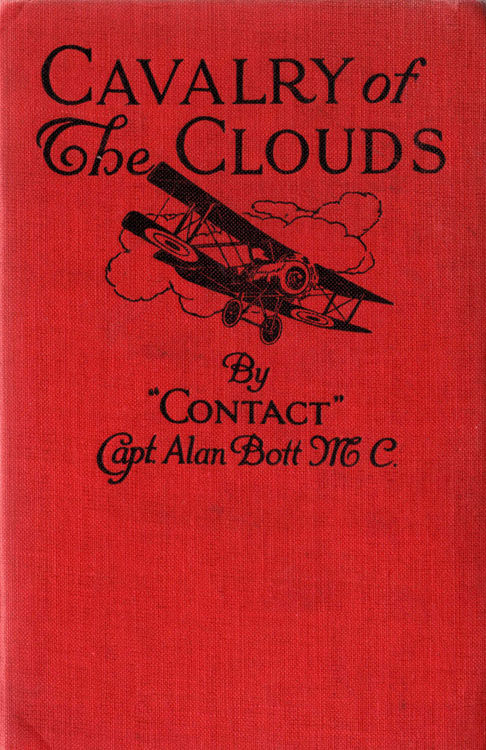

CAVALRY OF THE CLOUDS

CAVALRY OF THE CLOUDS

BY

"CONTACT"

(Capt. Alan Bott, M.C.)

With an introduction by

Major-General W. S. BRANCKER

(Deputy Director-General of Military Aëronautics)

Garden City — New York

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1918

Copyright, 1917, by

Doubleday, Page & Company

All rights reserved,

including that of translation into foreign languages,

including the Scandinavian

DEDICATED

TO

THE FALLEN OF UMPTY SQUADRON, R.F.C.

JUNE-DECEMBER 1916

PREFACE

Of the part played by machines of war inthis war of machinery the wider public hasbut a vague knowledge. Least of all does itstudy the specialised functions of army aircraft.Very many people show mild interestin the daily reports of so many Germanaeroplanes destroyed, so many driven down,so many of ours missing, and enraged interestin the reports of bomb raids on Britishtowns; but of aerial observation, the mainraison d'etre of flying at the front, they ownto nebulous ideas.

As an extreme case of this haziness overmatters aeronautic I will quote the lay question,asked often and in all seriousness: "Canan aeroplane stand still in the air?" Anothersurprising point of view is illustratedby the home-on-leave experience of a pilotbelonging to my present squadron. Hislunch companion—a charming lady—said she[Pg viii]supposed he lived mostly on cold food whilein France.

"Oh no," replied the pilot, "it's much thesame as yours, only plainer and tougher."

"Then you do come down for meals," deducedthe lady. Only those who have flownon active service can fully relish the comicsavour of a surmise that the Flying Corpsin France remain in the air all day amid allweathers, presumably picnicking, betweenflights, off sandwiches, cold chicken, porkpies, and mineral waters.

These be far-fetched examples, but theyserve to emphasise a general misconceptionof the conditions under which the flyingservices carry out their work at the big war.I hope that this my book, written for themost part at odd moments during a fewmonths of training in England, will suggestto civilian readers a rough impression of suchconditions. To Flying Officers who honourme by comparing the descriptions with theirown experiences, I offer apology for wh