the ethicators

BY WILLARD MARSH

They were used to retarded life forms, but

this was the worst. Yet it is a missionary's duty

to bring light where there is none, for who can

tell what devious forms evolution might take?

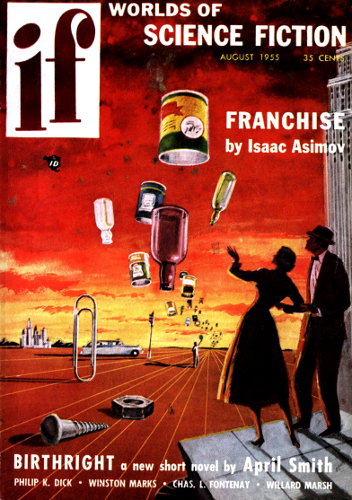

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, August 1955.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The missionaries came out of the planetary system of a star they didn'tcall Antares. They called it, naturally enough, The Sun—just as homewas Earth, Terra, or simply The World. And naturally enough, being theascendant animal on Earth, they called themselves human beings. Theywere looking for extraterrestrial souls to save.

They had no real hope of finding humans like themselves in thiswonderously diversified universe. But it wasn't against all probabilitythat, in their rumaging, there might not be a humanoid species to whomthey could reach down a helping paw; some emergent cousin with at leasta rudimentary symmetry from snout to tail, and hence a rudimentary soul.

The ship they chose was a compact scout, vaguely resembling the outsideof an orange crate—except that they had no concept of an orange crateand, being a tesseract, it had no particular outside. It was simply anexpanding cube (and as such, quite roomy) whose "interior" was alwaysparalleling its "exterior" (or attempting to), in accordance with allthe well-known, basic and irrefutable laws on the subject.

A number of its sides occupied the same place at the same time, givinga hypothetical spectator the illusion of looking down merging sets ofrailway tracks. This, in fact, was its precise method of locomotion.The inner cube was always having to catch up, caboose-fashion, withthe outer one in time (or space, depending on one's perspective).And whenever it had done so, it would have arrived with itself—atapproximately wherever in the space-time continuum it had been pointed.

When they felt the jar of the settling geodesics, the crew crowded atthe forward visiplate to see where they were. It was the outskirts ofa G type star system. Silently they watched the innermost planet floatpast, scorched and craggy, its sunward side seeming about to relapse toa molten state.

The Bosun-Colonel turned to the Conductor. "A bit of a disappointmentI'm afraid, sir. Surely with all that heat...?"

"Steady, lad. The last wicket's not been bowled." The Conductor'swhiskers quivered in amusement at his next-in-command's impetuosity."You'll notice that we're dropping downward. If the temperatureaccordingly continues dropping—"

He couldn't shrug, he wasn't physiologically capable of it, but it wasapparent that he felt they'd soon reach a planet whose climate couldsupport intelligent life.

If the Bosun-Colonel had any ideas that such directions as up anddown were meaningless in space, he kept them to himself. As the secondplanet from its sun hove into view, he switched on the magniscaneagerly.

"I say, this is more like it. Clouds and all that sort of thing. Shouldwe have a go at it, sir?"

The Conductor yawned. "Too bloody cloudy for my taste. Too equivocal.Let's push on," he said languidly. "I have a hunch the third planetmight be just our dish of tea."

Quelling his disappointment, the Bosun-Colonel waited for the thirdplanet to swim into being. And when it did, blooming like an orchidin all its greens and moistnesses, he could scarcely contain hisexcitement.

"Why, it