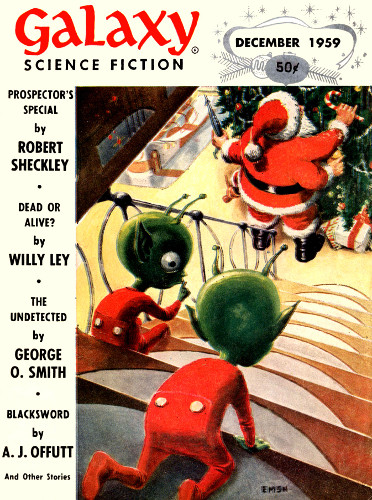

Charity Case

By JIM HARMON

Illustrated by DICK FRANCIS

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction December 1959.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Certainly I see things that aren't there

and don't say what my voice says—but how

can I prove that I don't have my health?

When he began his talk with "You got your health, don't you?" ittouched those spots inside me. That was when I did it.

Why couldn't what he said have been "The best things in life are free,buddy" or "Every dog has his day, fellow" or "If at first you don'tsucceed, man"? No, he had to use that one line. You wouldn't blame me.Not if you believe me.

The first thing I can remember, the start of all this, was when I wasfour or five somebody was soiling my bed for me. I absolutely was notdoing it. I took long naps morning and evening so I could lie awake allnight to see that it wouldn't happen. It couldn't happen. But in themorning the bed would sit there dispassionately soiled and convict meon circumstantial evidence. My punishment was as sure as the tide.

Dad was a compact man, small eyes, small mouth, tight clothes. He wasnarrow but not mean. For punishment, he locked me in a windowlessroom and told me to sit still until he came back. It wasn't so bad apunishment, except that when Dad closed the door, the light turned offand I was left there in the dark.

Being four or five, I didn't know any better, so I thought Dad made itdark to add to my punishment. But I learned he didn't know the lightwent out. It came back on when he unlocked the door. Every time I toldhim about the light as soon as I could talk again, but he said I waslying.

One day, to prove me a liar, he opened and closed the door a few timesfrom outside. The light winked off and on, off and on, always shiningwhen Dad stuck his head inside. He tried using the door from theinside, and the light stayed on, no matter how hard he slammed thedoor.

I stayed in the dark longer for lying about the light.

Alone in the dark, I wouldn't have had it so bad if it wasn't for thethings that came to me.

They were real to me. They never touched me, but they had a little boy.He looked the way I did in the mirror. They did unpleasant things tohim.

Because they were real, I talked about them as if they were real, andI almost earned a bunk in the home for retarded children until I gotsmart enough to keep the beasts to myself.

My mother hated me. I loved her, of course. I remember her smell mixedup with flowers and cookies and winter fires. I remember she hugged meon my ninth birthday. The trouble came from the notes written in myawkward hand that she found, calling her names I didn't understand.Sometimes there were drawings. I didn't write those notes or make thosedrawings.

My mother and father must have been glad when I was sent away to reformschool after my thirteenth birthday party, the one no one came to.

The reform school was nicer. There were others there who'd had it aboutlike me. We got along. I didn't watch their shifty eyes too much, orask them what they shifted to see. They didn't talk about my screamsat night.

It was home.

My trouble there was that I was always being framed for stealing. Ididn't take any of those things they located in my bunk. Stealingwasn't in my line. If you believe any of this at all, you'll see why itcouldn't be me who did