THE RECLUSE

By MIKE CURRY

The human voice! Had there even been

so sweet a sound? Arak Miller ached

for it—too eagerly; too swiftly.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Winter 1954.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Twenty-five years later a ship appeared, on an afternoon in theplanet's summer.

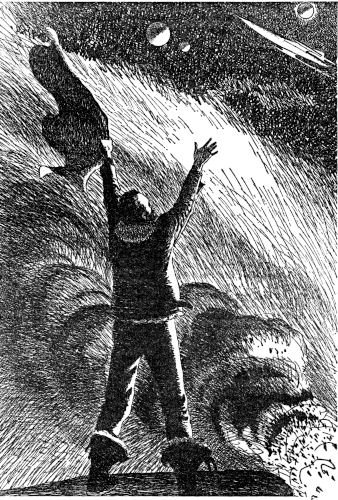

Arak Miller watched it from the mesa.

From Earth, he thought. From Earth!

But Arak Miller was an ordered man. Even now, in the face of resurgingvisions of his wife, and his sons, and his work, and the mightycivilization from which he had been cut adrift, his thoughts wereordered: probably the ship had arrived from Earth to resurvey one ofthe Class II uninhabitable planets of the Alpha Centaurus System.Tomorrow its scout ships would whip along the day sides at fivethousand feet. Tomorrow atop the mesa he must light his pyres, somehundred-odd gigantic piles of pine trees and brush that would burn withbillowing smoke. He must signal the presence of a lone Earthman.

With a hypnotic intensity he stood watching the ship until, towardevening, it merged into the gray sky over the horizon. Then he ranacross the clearing and down to his house by the river that woundthrough the valley a thousand feet below. "Come on, you fool!" heshouted to Marbach, sitting beneath a tree. Arak Miller threw thefigure over his shoulder and carried him to the house. He sat Marbachon a chair and went into the kitchen to eat.

Arak Miller had been nomadic the first few years after he crashed andhad been abandoned for dead, until he found in the planet's narrowtemperate zone one of the few arable regions capable of sustaining him.There was sufficient small game, the river was cool, and because therain fell mainly in the valley, his pyres were safe.

In recent years he was always building. He had added a front porch tothe cabin he had started with, then more rooms which he had neverused, then an attic into which he never went. Now it was a house. Ithad chairs and tables, a bed, a rug of vines, a garden for vegetablesand tobacco, and a garden for flowers.

He ate a leisurely meal of potatoes and corn and meat of therabbit-like creatures which he trapped. Miss Gormeley was sitting onthe porch as he went out. "A ship's come," he shouted. "I may be saved,you understand?"

He recalled he had intended to do something about Miss Gormeley'snostril. With one of his knives he scraped a little against the wall ofher left nostril. Then he stood back, satisfied. "Now you look better,"he said. With a wry grin he added, "You can smell better, too."

For a long time he could not sleep, remembering that he had been cutoff in the prime of his life. He had been the Senior Astrophysicistin the Systems War Office on Earth, working on the Second EinsteinModifications that promised travel to the more distant galacticSystems. He had completed six months of comparison spectography in thebarren Centaurus System and had been about to take the year's returnjourney to Earth, looking forward to a vacation trip with his family toVenus City. He had been in the forefront of the free world's pushingback of the last frontiers of man.

He twisted on his bed in a wild agony of hope and yearning. "Somedaysoon," he shouted to the walls, "I'll ride the monorail across theWestern plains." He had discovered that it helped, to talk aloud,though none of his devices could make him forget he was a prisoner. Tofee