ONE WAY

By MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD

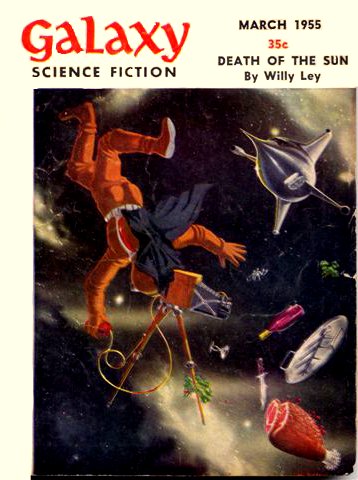

Illustrated by Irv DOCKTOR

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Galaxy Science FictionMarch 1955. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that theU.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

We had the driver let us off in the central district and took acopter-taxi back to Homefield. There's no disgrace about it, of course;we just didn't feel like having all the neighbors see the big skycarwith Lydna Project painted on its side, and then having them drop incasually to express what they would call interest and we would know tobe curiosity.

There are people who boast that their sons and daughters have beenpicked for Lydna. What is there to boast about? It's pure chance, withinlimits.

And Hal is our only child and we love him.

Lucy didn't say a word all the way back from saying good-by to him. Lucyand I have been married now for 27 years and I guess I know her about aswell as anybody on Earth does. People who don't know her so well thinkshe's cold. But I knew what feelings she was crushing down inside her.

Besides, I wasn't feeling much like talking myself. I was rememberingtoo many things:

Hal at about two, looking up at me—when I would come home dead-tiredfrom a hard day of being chewed at by half a dozen bosses right up tothe editor-in-chief whenever anything went the least bit out ofkilter—with a smile that made all my tiredness disappear. Hal, when I'dpick him up at school, proudly displaying a Cybernetics Approval Slip(and ignoring the fact that half the other kids had one, too). Hal theday I took him to the Beard Removal Center, certain that he was a man,now that he was old enough for depilation. Hal that morning two weeksago, setting out to get his Vocational Assignment Certificate....

That's when I stopped remembering.

It had been five years after our marriage before they let us start achild: some question about Lucy's uncle and my grandmother. Most parentsaren't as old as we are when they get the news and usually have otherchildren left, so it isn't so bad.

When we got home, Lucy still was silent. She took off her scarf andcloak and put them away, and then she pushed the button for dinnerwithout even asking me what I wanted. I noticed, though, that she wasordering all the things I like. We both had the day off, of course, togo and say good-by to Hal—Lucy is a technician at Hydroponics Center.

I felt awkward and clumsy. Her ways are so different from mine; Iexplode and then it's over—just a sore place where it hurts if I touchit. Lucy never explodes, but I knew the sore place would be thereforever, and getting worse instead of better.

We ate dinner in silence, though neither of us felt hungry, and had thetable cleared. Then it was nearly 19 o'clock and I had to speak.

"The takeoff will be at 19:10," I said. "Want me to tune in now? Lastyear, when Mutro was Solar President, he gave a good speech before thekids left."

"Don't turn it on at all!" she said sharply. Then, in a softer voice,she added: "Of course, Frank, turn it on whenever you like. I'll just goto my room and open the soundproofing."

There were still no tears in her eyes.

I thought of a thousand things to say: Don't you want to catch a glimpseof Hal in the crowd going up the ramp? Mightn't they let the kids wave alast farewell to their folks listening and watching in? Mightn'tsomething