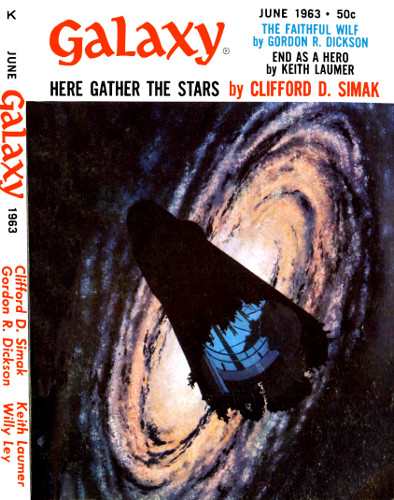

END AS A HERO

By KEITH LAUMER

Illustrated by SCHELLING

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction June 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Granthan's mission was the most vital of the war.

It would mean instant victory—but for whom?

I

In the dream I was swimming in a river of white fire and the dream wenton and on. And then I was awake—and the fire was still there, fiercelyburning at me.

I tried to move to get away from the flames, and then the real painhit me. I tried to go back to sleep and the relative comfort of theriver of fire, but it was no go. For better or worse, I was alive andconscious.

I opened my eyes and took a look around. I was on the floor next toan unpadded acceleration couch—the kind the Terrestrial Space Arminstalls in seldom-used lifeboats. There were three more couches, butno one in them. I tried to sit up. It wasn't easy but, by applying alot more will-power than should be required of a sick man, I made it.I took a look at my left arm. Baked. The hand was only medium rare,but the forearm was black, with deep red showing at the bottom of thecracks where the crisped upper layers had burst....

There was a first-aid cabinet across the compartment from me. Itried my right leg, felt broken bone-ends grate with a sensationthat transcended pain. I heaved with the other leg, scrabbled withthe charred arm. The crawl to the cabinet dwarfed Hillary's trekup Everest, but I reached it after a couple of years, and found themicroswitch on the floor that activated the thing, and then I wasfading out again....

I came out of it clear-headed but weak. My right leg was numb, butreasonably comfortable, clamped tight in a walking brace. I put upa hand and felt a shaved skull, with sutures. It must have been afracture. The left arm—well, it was still there, wrapped to theshoulder and held out stiffly by a power truss that would keep the scartissue from pulling up and crippling me. The steady pressure as thetruss contracted wasn't anything to do a sense-tape on for replaying atleisure moments, but at least the cabinet hadn't amputated. I wasn'tcomplaining.

As far as I knew, I was the first recorded survivor of contact with theGool—if I survived.

I was still a long way from home, and I hadn't yet checked on thecondition of the lifeboat. I glanced toward the entry port. It wasdogged shut. I could see black marks where my burned hand had been atwork.

I fumbled my way into a couch and tried to think. In my condition—witha broken leg and third-degree burns, plus a fractured skull—Ishouldn't have been able to fall out of bed, much less make the tripfrom Belshazzar's CCC to the boat; and how had I managed to dog thatport shut? In an emergency a man was capable of great exertions. Butrunning on a broken femur, handling heavy levers with charred fingersand thinking with a cracked head were overdoing it. Still, I washere—and it was time to get a call through to TSA headquarters.

I flipped the switch and gave the emergency call-letters Col. AusarKayle of Aerospace Intelligence had assigned to me a few weeks before.It was almost five minutes before the "acknowledge" came through fromthe Ganymede relay station, another ten minutes before Kayle's faceswam into view. Even through the blur of the screen I could see thehaggard look.

"Granthan!" he burst out. "Where are the others? What h