You too can cause earthquakes, munch

high-tension power lines and travel faster

than light—all you have to do is become an

E being

BY JAMES STAMERS

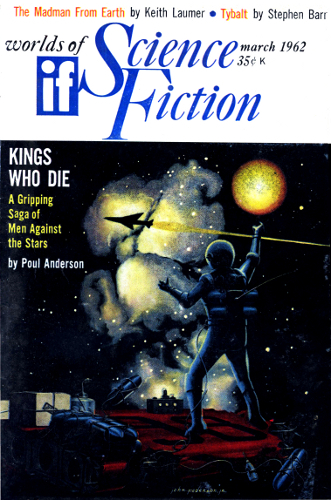

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, March 1962.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

First man to reach the speed of light, I was. But you'll find the goodAlbert only hinted at the effects, in a delta-theta 2.3 pi-squaredway. E=mc2, he said. And for fifty years before they built my rocket,the Lighttrick, slim, tapering, sleek and gy-perpowered, everyoneconcentrated on turning matter into energy at a light-squared power.Big, bright bangs, and congratulations.

It's a pity no one asked what happens to energy divided by the speedof light. I happen to be the answer to the equation, and by interferingwith the motor of this electric typescripter I can give you my thoughtson the matter.

The Lighttrick hit full velocity out there between Van Allen and theasteroids. I'd guess the whole beautiful ship, including me, convertedinto energy and, slowing down, reconverted on the wrong side, so tospeak. And there I was, floating without a ship and surrounded bylittle round beings, shimmering in a blue haze.

"Good afternoon," I said.

But no sound came out of my mouth. I had a mouth, in a way, but not fortalking; and not at all the sort of mouth I used to have. In fact, theshimmering blue haze was me. I could find no other parts of me. Andwhen the little round things touched me on the periphery, there was anintelligent vibration.

"Frequency and tone?" said the vibration. "Please identify."

"You must take me as you find me," I thought.

"Unidentified frequencies and discordant tones requested not to wanderin spaceways," vibrated the little round things.

"I'm a man," I vibrated back. "We don't have frequencies. We usefrequencies in radio, television, radar and so on."

"Not intelligible."

"Where's my ship?"

"Ship?"

I tried to picture the Lighttrick and the long thin gleam on herhull, the fury of her rockets and the calm ordered keyboard of thecontrol panels.

"Most interesting," vibrated the round things. "Poetic. Very creative.Speculative philosopher, yes?"

They seemed to be grasping the general idea, so I concentrated on animage of myself, square and bearded, staring sternly into space throughthe ports, in a pioneer manner, observing hitherto unknown planets.

"Most ingenious," my audience vibrated back. "But unlikely."

Then they started vibrating among themselves.

"Senior e minus says...."

"Mush is mush, that's what I say."

"Now, theoretically...."

"I don't vibrate why not. There are more things in positive andnegative, Horatio, than...."

"Excuse me," I vibrated.

There was a brief pause.

"Perhaps we should illuminate."

"Please do," I vibrated politely.

They gathered round the edges of my haze and explained. It seemeda very senior e had suggested once that there might, just might,theoretically be side-effects of mush. The little round things were ebeings. And "mush" was the accepted term for the static and orbitaltracks of electrons in fixed patterns, such as one found here and therein space. But the very senior e, apparently, had speculated that ina certain narrow band of light frequencies mush might possibly givean appearance of "matt